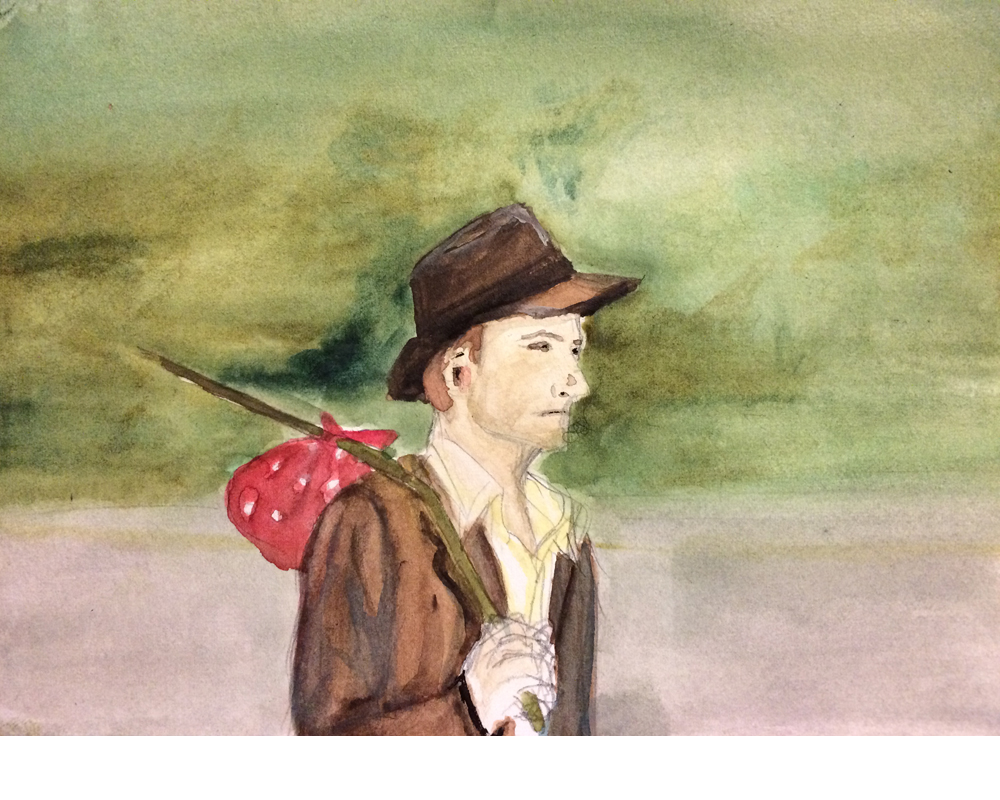

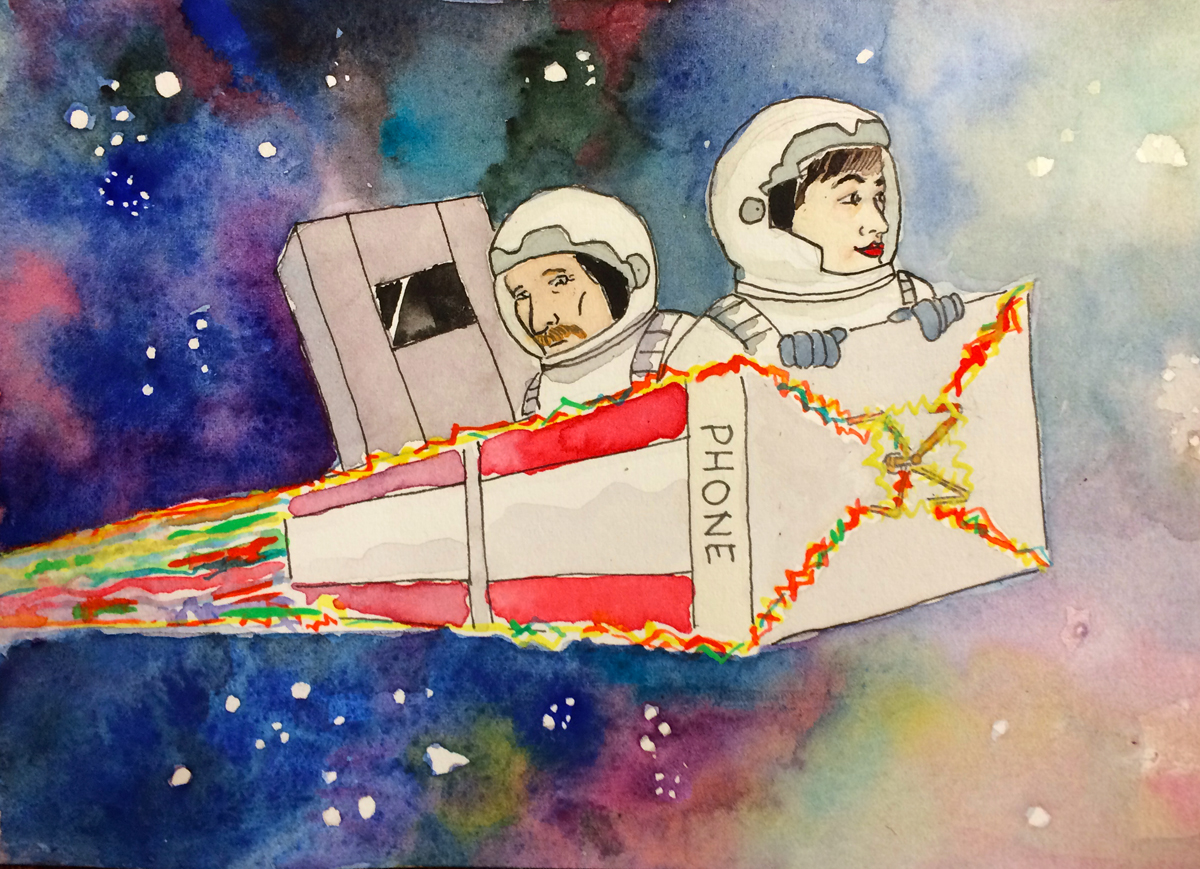

ILLUSTRATION: Sullivan’s Travels • watercolor • 5×7″

Last year my friend Bryan suggested I read Michel Houellebecq’s 2005 novel The Possibility of an Island which I didn’t enjoy very much at all. That said, his recommendation may very well have been, “This novel is very dark, and you’re probably going to hate it. It’s a really hateful book.” John Updike’s book review was titled “90% Hateful.” So it’s not like I should have been surprised.

The main character Daniel is a successful French comedian who specializes in shock comedy aimed at various religions, especially Islam. In a tale as old as time, Daniel falls out of love with his wife, in love with a 22-year-old Spanish girl, and then joins and helps lead a futuristic sex cult obsessed with cloning (or a cloning cult obsessed with sex, it’s hard to say). The progression to dystopia is half narrated by two asexual clones living in the future, creating a story that feels as if you mixed a Lars Von Trier movie with a Paul Verhoeven one, then paid for a novelization by Haruki Murakami in his most unfeeling prose with Bret Easton Ellis as translator, perhaps adding his own disturbing sexual flourishes.

I’d like to hope that the whole of the book’s cynicism is trenchant satire (which I’m ashamed to admit I sometimes miss in practice), but I’m afraid that often Houellebecq may be projecting his worldview quite directly in passages such as this one:

“Like the revolutionary, the comedian came to terms with the brutality of the world, and responded to it with increased brutality. The result of his action, however, was not to transform the world, but to make it acceptable by transmuting the violence, necessary for any revolutionary action, into laughter—in addition, also, to making a lot of dough. To sum up, like all clowns since the dawn of time, I was a sort of collaborator. I spared the world from painful and useless revolutions.”

There’s a lot here to be unpacked, but in summary, Houellebecq gives us no way to win—the complicit comedian forestalls revolution, sublimating people’s anger, while the revolutionary is engaged in a “painful and useless” enterprise. It denies the possibility of change at all. What we have is where we’ll stay, or, in the context of the book, will only get worse. And that’s just one bitter paragraph among 300 pages full of them. Screw you Michel Houellebecq and your portrait of an artist as a middle-aged sellout.

Yet I’ve been thinking a lot about this passage in the last week after the shooting in Paris, thinking about outrage and violence as the emotional counterpoint to laughter. Although feelings of outrage can drive necessary social change, the emotion’s lack of nuance may also be the breeding ground of mob rule and totalitarianism. Sometimes it occurs to me (and frightens me) that outrage might be the defining emotion of our Internet age—the emotion of demagoguery, of participatory hashtags, of surprise over completely-to-be-expected human weakness, of overly earnest agreement, and overly bombastic disagreement. As my friend Inga suggests, we don’t live in a world full of irony, but rather we often live in a world where it’s completely lacking.

It’s occurred to me that if “comedy equals tragedy plus time,” perhaps then laughter equals outrage plus perspective. To improve our lot, it’s perspective we need more of, not outrage. And in that world, comedy is hardly a collaborator to anything we want to avoid.

What books did you read in 2014? What books do you plan to read in 2015? Do you hate Michel Houellebecq? Comment away. Or not. That’s cool too. Happy 2015!